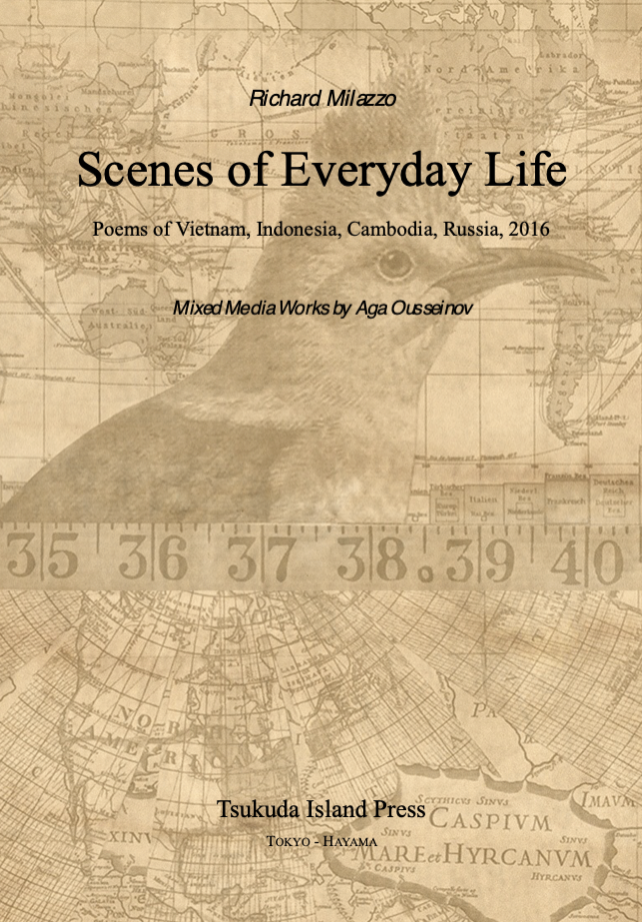

Scenes of Everyday Life: Poems of Vietnam, Indonesia, Cambodia, Russia, 2016

by Richard Milazzo

With 64 black and white reproductions of Aga Ousseinov’s mixed media collages from his latest series of works, Celestography, as well as images of his sculptures and various details from his installations – some of them deriving from his participation in the 54th edition of the Venice Biennale, and from the artist windows project he designed for Hermes of Paris, edited and with an introduction and commentary by Richard Milazzo.

First edition paperback: February 2020.

Designed by Richard Milazzo.

208 pages, with a gatefold color cover reproducing a work by Aga Ousseinov, a black and white collage of the author and the artist by the artist on the frontispiece.

9.25 x 6.5 in., printed, sewn and bound in Savignano-sul-Panaro, Italy.

ISBN: 1-893207-46-3.

ISBN: 879-1-893207-46-2.

Hayama and Tokyo, Japan: Tsukuda Island Press, 2020.

Published on the occasion of the exhibition, Aga Ousseinov: Celestography at the New York Public Library, 18 West 53rd St. Branch N.Y.

February 4 - March 31, 2020.

RETAIL PRICE: $24.00 (includes postage and handling)

No story could be more dramatic than Aga Ousseinov’s: “My father’s family have been sailors for a hundred and fifty years, until the first quarter of the 20th century. And by the time of the Russian Revolution in 1917 (and, in the Caucasus, in 1920), they were major ship owners in Baku on the Caspian Sea. In the mid 1970s, my father, while working in the archives, found copies of blueprints for ships owned by our family that were made at Stockholm shipyards in Sweden. Later, during the Russian Civil War (1918-1920), one of our ships was transferred to the command of the Royal Air Force (UK) and converted into one of the first aircraft carriers. Perhaps these stories about my family somehow explains my interest in the maritime and aeronautical themes. My mother was a specialist in Russian Constructivism and other early twentieth-century art movements in Central and Western Europe.

“Through this exposure, I developed an interest in Italian Futurism, the Russian avant-garde, Dada and Bauhaus, and artists such as Rodchenko, Duchamp, El Lissitsky, Tatlin, and Fortunato Depero. I found inspiration in posters, industrial design, window dressing, and automobile and aircraft design. Other early influences and inspirations include Minoan and Etruscan Art, early Renaissance art, the painter Niko Pirosmani, films by Georges Méliès, Sergei Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov, and, in literature, Tommaso Campanella’s Citta del Sol, Raymond Roussel, Mikhail Bulgakov, and George Orwell.

“After that the Soviet Army drafted me and I served eighteen months, where I made historical military dioramas, a statue of Lenin, and worked on the restoration of patriotic sculptures from the 1930s for the Moscow Military Museum (these were mostly statues of the first Soviet aviators).

“I left for New York in 1991. During my first few years, I made a living by constructing architectural models, design prototypes, wooden marionettes and set designs. I worked also as an assistant for Ilya Kabakov, Not Vital, Saint Clair Cemin and Donald Baechler. These last three decades have been a fantastic voyage. And New York is where I continue to live and work. And what a ride it has been! It feels like I boarded one of those early flying contraptions I made when I was seven, and never got off! An impossible voyage, but one that I continue to enjoy.”

The poems in Scenes of Everyday Life: Poems of Vietnam, Indonesia, Cambodia, Russia, 2016, by Richard Milazzo, received their descriptive title from the silk paintings of Vietnam the author saw in Cambodia. The contemporary artist, Aga Ousseinov, born in Baku, Azerbaijan (former USSR), working and living in the U.S. since 1991, has appended to the 64 poems in the book reproductions of his collages from his latest series of works, Celestography, as well as images of his sculptures and various details from his installations – some of them deriving from his participation in the 54th edition of the Venice Biennale, and from the artist windows project he designed for Hermes of Paris.

In his introduction, the author writes: “The poems written in Jakarta and Yogyakarta pulse with romance and erotic encounters in Sunda Kelapa, the bird market (Taman Sari), and the Sambisari Temple. Unexpected was the laughter reverberating in the niches of Borobudur, contradicting the meditative affectations more commonly the experience in such places; the challenge of the Two Ficus trees in Yogyakarta (the blind leading the blind); and the indulgence of the water and pleasure gardens despite the ruination brought upon them by the vengeful goddess, Kali. Concluding the journey was an erotic adventure in Prambanan Temple and an unforgettable visit to Tjong A Fie Mansion in Medan (Sumatra).”

In Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s “secret city,” the author experienced hallucinations, “ungodly gods,” and a “songbird – or what amounts to a man – / tortured by what it had swallowed, / what every man inevitably has to swallow.” “The Cannibalism of Metaphor” records the poet’s “refus[al] to mask, to bury, hunger’s deepest realities, / the demise it proffers, in metaphor.” There is the story about the desperate hunger of the body invariably accompanied by the desperate loneliness of the soul”; a poem about the author’s passing and a rather caustic meditation about history being “comprised of facts / gone awry / swaddled in the arms of an unloving girl.” Perhaps the Chinese are right, what could matter more than the absurdities of life.

In Petersburg, there obtain erotics in the Summer Gardens in winter and in the Church of the Spilt Blood; a moving visit to Anna Akhmatova’s apartment; and sightings of Raskolnikov and the Grand Duchess Tatyana Nikolaevna. A visit to Tsarskoye Selo results in apocryphal stories about Kafka and Rachmaninoff. Milazzo: “I do not see much point in writing a poem if it does not tell a story. On the other hand, there are always formal or lyrical urges that are both welcome and a danger to the narrative, if they pull it too much in the direction of the oblivion (the eradication of the self) by which they always seem to be seduced. How this threshold differs from the attempted instantiation of a private language eludes me. I suppose it is about finding a balance. Easier said than done.

“This is not an argument for commonness; it is an appeal for the common ground we all stand on. If we have to wait for a death-bed conversion to understand this, then we are really in for a major disappointment. I guess we can call this outcome the reward of an unexamined life. What we have to show for an examined one, well, that is up for grabs, too.

“When it comes to the role of story in poetry and the beauty and intensity of its (poetry’s) lyrical dimension, and its metaphorical capacity, especially operative at its most extreme thresholds, it is difficult to decide in favor of one over the other, at least for me. Perhaps my compromise comes in the form of no longer believing in metaphor or simile apropos of something being like something else. Either something is (itself) or it isn’t.”

The author writes: “As for the relation between the poems and the images in this book: sometimes I see it, sometimes I don’t. Like my shadow. I did not do the pairing. I asked Aga to do this difficult, if not impossible, task, knowing in advance and unfairly it was impossible. Frankly, I don’t think it is so important. I feel a great sympathy for Aga’s work, and that is really all that matters. And he may have felt the same way about mine. Although if you think about it even a little, what does the “celestial” realm have to do with “scenes of everyday life” in any sense? And there are even an ample number of instances where there are disagreements between Ousseinov’s intentions and my interpretations. Rather than incorporating his view into my text, I have often simply openly cited his take on the matter at hand. Talk about the true dialectical method and the difficulty of finding and standing on common ground. And, in addition, if we did not really compromise to make it – the pairings as a collective aesthetic machine, and the couplings of our intentions and interpretations – work, perhaps we are both, in some sense, uncompromised. Wouldn’t that be a vaguely good thing, no matter how unsuccessful?”

Besides the extensive introduction and commentary on Ousseinov’s work, the author and editor of Scenes of Everyday Life has included five expository texts by the artist and by Stephen Dean, Diana Ewer, and Veronika Sheer, along with a comprehensive exhibition history and bibliography. The front and back covers and the frontispiece were especially created by the artist for the book.