Le Violon d’Ingres: Sunday Poems and Lineations 1993-1996

by Richard Milazzo.

First edition paperback: October 2004.

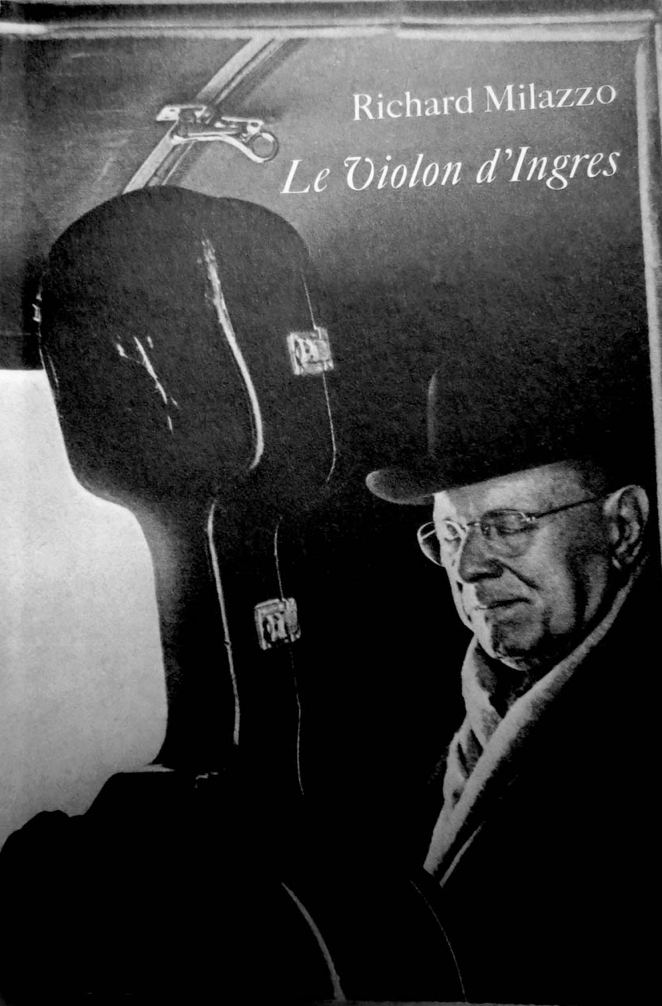

96 pages, with a black and white photograph of the author by Joy L. Glass, Paris, December 1993, on the frontispiece, and a portfolio of 8 black and white photographs by the author.

7.25 x 4.75 in., printed, sewn and bound in Turin, Italy.

ISBN: 88-88454-09-8.

Published by Night Mail, Bomarzo, Italy, 2004.

RETAIL PRICE: $20.00 (includes postage and handling)

Le Violon d’Ingres: Sunday Poems and Lineations 1993-1996 is Richard Milazzo’s first book of poetry. After a hiatus of twelve years, he returned to writing poetry in 1993. He had written poetry from 1967 to 1981, before he unaccountably stopped. Le Violon d’Ingres is an unacknowledged tour de force, in that it rejects the avant-garde Language-writing principles of his generation (even where traces of it are still present, here and there, in this volume), which had become academic by the time he returned to poetry, even as he attempted to deviate from the Modernist parameters of free verse established by Ezra Pound, embracing abstraction and the lyrical in poetry while still holding on to story and the narrative function. “Mauberley Descended”: “You must kill / to forge Archaia / all that is media-bound / and information-ended. // You must leave / the image senseless / if you are to pound / new meaning ascendant.” This short lyric is manifesto-like in lobbying against “imagism” within the new sound-bite and media-bound culture.

Besides “Mauberley Descended,” other seminal poems in the volume are “The Man in a Plain White T-Shirt,” “Classic Anedote,” “A Love Poem,” “Poetry,” “The Ambassador of Dreams,” and “Cimetière de Passy.”

Much of Le Violon d’Ingres was written in Paris, and outside New York City, where the writer lives, and published in Italy. His love of travel will become still more apparent in his later books.

The subtitle, Sunday Poems and Lineations, clearly indicates the writer’s self-doubts and sporadic indecision about his return to writing verse. Nonetheless he remains self-assured throughout the volume, adopting a diverse range of experimental and classical forms.

Le Violon d’Ingres does not shy away from emotion, yet it is disciplined. The literary references are considerable but unobtrusive. And it is equally replete with a sense of gravitas and the absurd, evidenced in both instances by the number of epitaphs the author has written in relation to his own death. “Venice”: “The wind / is a clown / in your closet.”