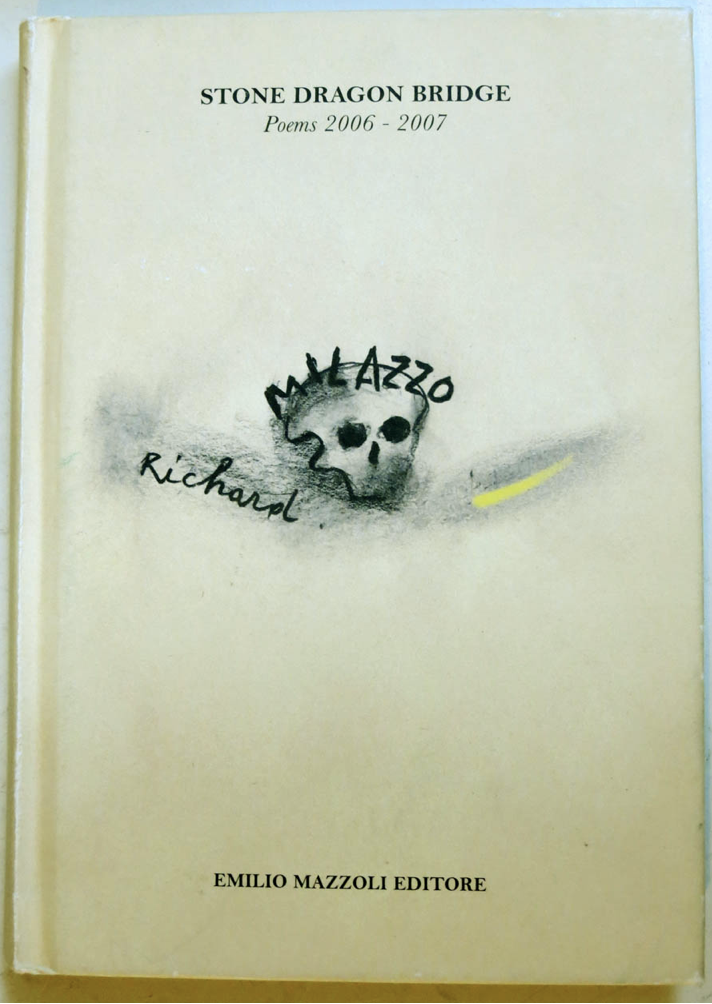

Stone Dragon Bridge: Poems of China 2006-2007

by Richard Milazzo.

With an Italian translation and preface by Brunella Antomarini.

First edition hardcover: 2007.

116 pages, 500 numbered copies, with an original cover by Enzo Cucchi, a sepia-toned photograph of the author on the Lijiang River, China, January 2007, by Joy L. Glass on the frontispiece, and a cyan-toned photograph by the author.

6.75 x 5 in., printed, sewn and bound in Savignano sul Panaro, Modena, Italy.

Published by Emilio Mazzoli Editore, Modena, Italy, 2007.

RETAIL PRICE: $40.00 (includes postage and handling)

Richard Milazzo’s Stone Dragon Bridge: Poems of China 2006-2007 documents the author’s first trip to China. In Beijing, he seeks out the remaining hutongs (alleyways) and siheyuan (courtyard houses) of old Peking. In Shanghai, he gazes down the Bund at night from his hotel room and tries to imagine what this famous boulevard was like before it was architecturally redimensionalized in the name of progress. He bemoans the loss of the Old Pudong district, a backwater area located on the east bank of the Huangpu River (bisecting Shanghai and intersecting the Yangzi River downstream) facing the Bund, once the city’s poorest quarter, filled with slums and brothels, now razed to the ground, assigned the status of Special Economic Zone, and become one of the largest development sites in the world – “a new kind of corporate slum filled with nothing but glass and steel skyscrapers.” He visits Xi’an, in Shaanxi province, which was, in the 9th century, the largest and richest city in the world, and the starting point of the Silk Road; and Guilin, in Guangxi province, and journeys along the Lijiang River in Southwest China, known for its karst peaks, which have inspired painters and poets for centuries.

The Italian philosopher Brunella Antomarini writes of the poet’s work: “he describes the memories of a journey in which the time of a lived experience is confused with historical time, the pleasure of a gaze embraces centuries of dramatic events, and the corporeal pace is at one with the pace of writing: ‘Walking became a style of writing, /... / leaving nothing but the sudden caesura / or slow chasm, indeed, / the measured enjambment of mortality.’ From verse to verse, from one language to the other, the vision of a internalized political condition unfolds, through a mediated perception, for the sake of an authentically felt poetry, seemingly exhaled from earth itself and making its terrible moral weight bearable to us.”